The Prince once asked me, ‘How on earth did Shakespeare manage it? I am Prince of Wales. Shakespeare wasn’t, but he knew exactly what it’s like. Exactly. How did he do it?’

In July 2022, not two months before the Queen’s death, along with the actress Dame Joanna Lumley, I hosted a happy lunch to mark Camilla’s 75th birthday. The guests were all friends and admirers, theatrical knights and dames, sports personalities and Chelsea Pensioners, Twiggy, Michael Palin and Andrew Lloyd-Webber – the usual suspects. The Duchess of Cornwall (as she then was) made a speech worthy of the Duke of Edinburgh. She talked about the year she was born, 1947, adding, ‘by the way, a vintage year for claret’. It was also, she told us, ‘the year when the first of the Ealing Comedies was released, the school leaving age was raised to fifteen, Gardeners’ Question Time was first broadcast, the University of Cambridge admitted women to full membership and soft loo paper went on sale for the first time, in Harrods – much to the nation’s relief.’ We laughed and then a hush fell as, deliberately, she paused before saying, ‘It was also in 1947 that the then Princess Elizabeth married Lieutenant Philip Mountbatten – two of the most remarkable people in our country’s history.’ Then, looking over the top of her glasses, she nailed her colours to the mast: ‘The Duke of Edinburgh’s philosophy was clear,’ she declared, ‘“Look up and look out, say less, do more – and get on with the job.” And that is just what I intend to do.’ And that is exactly what she has been doing this week and will continue to do in the months and years ahead.

==========

But I am mindful of the former prime minister James Callaghan’s observation: ‘What senior royalty offer you is friendliness, not friendship. There is a difference.’

==========

GB [author] (struggling): ‘The recession’s bad.’

HM [Queen] (looking grave): ‘Yes.’

GB (trying to jolly things along): ‘I think this must be my third recession.’

HM (nodding): ‘We do seem to get them every few years … and none of my governments seems to know what to do about them.’

==========

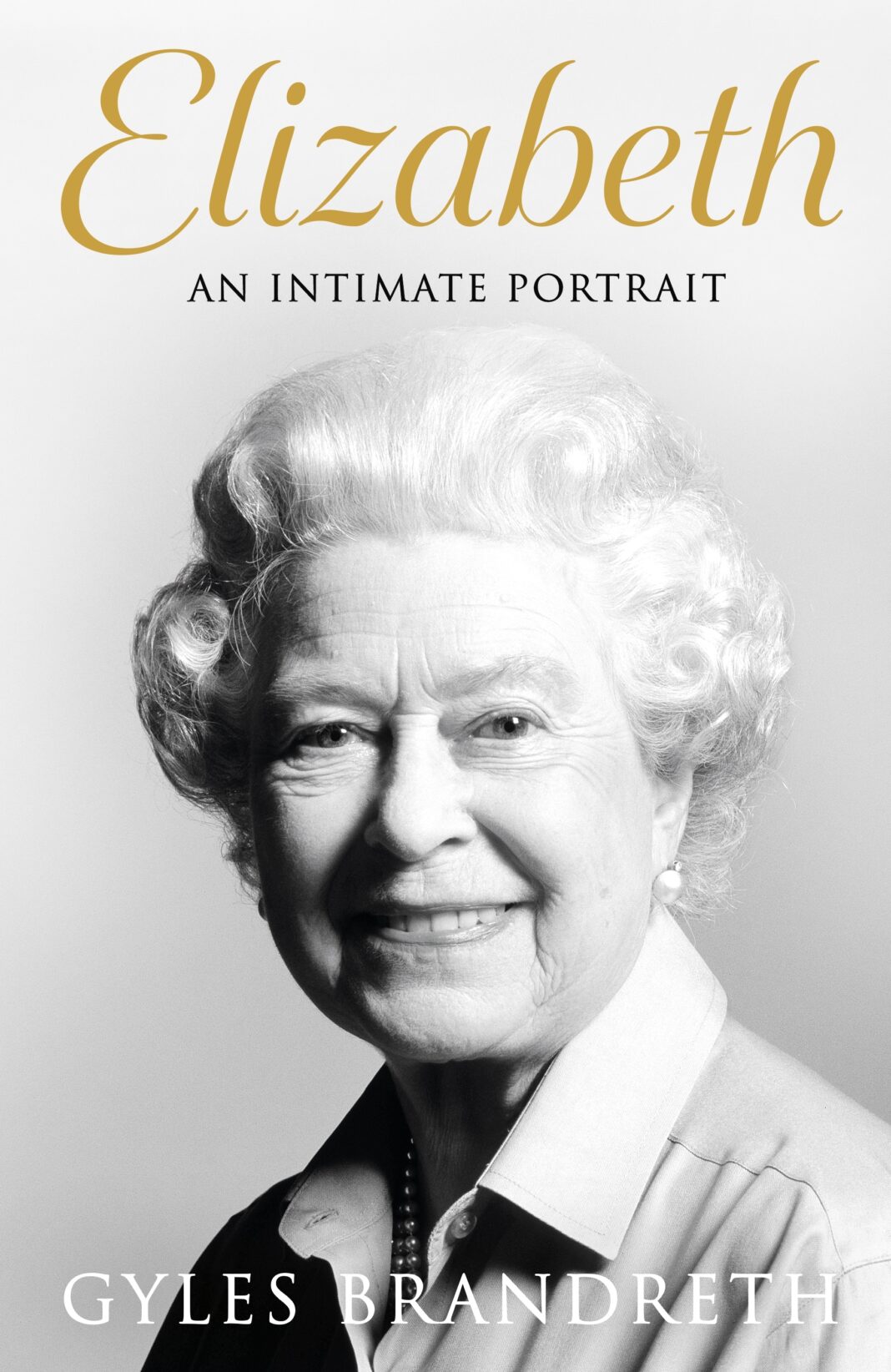

The Queen had a wry sense of humour. Her voice in conversation was softer, less artificial, less strangulated, than the voice we heard when she was opening Parliament or giving her Christmas Day broadcast. Physically, she was small, and became smaller with age, but, until her last years, she was sturdy. Close up, she always appeared younger than she was. Her dress sense and her helmet of permed silver hair may have come from a bygone era (increasingly she looked like her grandmother, Queen Mary), but her skin was good, and her make-up straightforward, simple, and modern.

==========

When I was travelling with the Queen’s party on one of her regional tours in 2001, we overheard someone in the crowd asking if the Duchess of Grafton, seated next to the Queen in the royal Bentley, was the Queen’s sister. This really delighted the Duchess. ‘I do feel like her sister,’ she said to me, proudly. They were very close. When the Duke of Grafton died, the Dowager Duchess moved to Whitelands House, a block of flats in London, on Cheltenham Terrace, just south of Sloane Square. Fellow residents were pleasantly surprised to occasionally see the Queen emerging from the lift after a visit to her old friend.

==========

‘We are all visitors to this time, this place,’ she said in a broadcast in the run-up to her Platinum Jubilee in 2022, when, inevitably, she knew she was not long for this world. ‘We are just passing through. Our purpose here is to observe, to learn, to grow, to love, and then we return home.’

==========

Victoria was more susceptible to flattery than Elizabeth. ‘Gladstone treats the Queen like a public department,’ said Benjamin Disraeli, ‘I treat her like a woman.’ Of course, Queen Victoria preferred Disraeli.

==========

George V, Elizabeth II’s grandfather, was a stickler for the established order of things – as his granddaughter was to be, by and large. As a boy, Prince George had been a naval cadet. He spent twenty years in the service and, according to his eldest son, throughout his life ‘retained a gruff, blue-water approach to all situations, a loud voice, and also that affliction common to Navy men, a damaged ear-drum.’ Apparently, ‘Damn fool!’ was his favourite expression. He had an explosive temper, a sailor’s simple sense of humour, and a horror of change for change’s sake. He liked things to be ‘ship-shape’; he appreciated order. He was a creature of habit: carefully, he checked the barometer, every morning and every night. When his wife, Queen Mary (as Princess May was known after the accession), attempted to shorten her skirts in line with the fashion of the day, the King would have none of it. As their eldest son recalled, ‘He disapproved of Soviet Russia, painted finger-nails, women who smoked in public, cocktails, frivolous hats, American jazz and the growing habit of going away for weekends

==========

David’s verdict on his father was a harsh one, possibly for understandable reasons, as we shall see in a moment. Bertie, the second son, was more respectful of his papa and Elizabeth, Bertie’s firstborn, simply loved her royal grandfather. She was only nine when George V died, but she told me she remembered him ‘with great affection’. ‘He was great fun,’ she said. As she also said, in a different context, ‘recollections may vary’ and the word ‘fun’ rarely occurs in other descriptions of George V. Famously, the diarist, diplomat and MP, Harold Nicolson, said that for many years, George ‘did nothing at all but kill animals and stick in stamps.’ Certainly, his stamp collection was his pride and joy and shooting the great passion of his life. (Elizabeth was fond of stamps, too, but not to the same degree.) As a man with a gun he was almost unstoppable. For example, in the seasons of 1902/03 and 1903/04, not long after he had become Prince of Wales, he counted up ‘What I shot’ and it was a total of more than 12,300 head of game each year – up from 11,000 in his list of ‘Game Killed by Me’ in 1896/97.

==========

Elizabeth II did not stamp her personality onto the events of her lifetime. She lived through times of unique change – the end of Empire, the end of the Cold War, the sexual revolution that came with the advent of oral contraception, the rise of feminism, the information technology revolution – but made no particular impact on them. Her achievement was not to set a tone or define a time, not to effect change or influence events. There were causes she espoused and themes that she returned to – notably the importance of the Commonwealth and the value of community and of service to others – but she was not a change-maker or a trend-setter. Her achievement was to be herself and, by being who she was, and by giving a lifetime of unwavering and consistent service to the country and the Commonwealth, to illustrate the value of her values of consistency, decency, service and dedication. Significantly, she signed her Platinum Jubilee message to her people: ‘Your Servant, Elizabeth R.’

==========

George Gage said of George V: ‘He was a very modest man personally, but he believed in the divine right of kings.’ Elizabeth II, too, was a very modest woman, but she accepted her destiny as Queen as a sacred duty. At her coronation in 1953, the moment when she was anointed with holy oil was for her the most sacred and significant part of the ritual – and the only part which, at her request, was not shown on television.

==========

For a king, George V was remarkably normal, too. On his accession in 1910, his first prime minister, Herbert Asquith, described him as ‘a nice little man with a good heart’, adding he ‘tries to be just and open-minded.’ David Lloyd George, as Chancellor of the Exchequer, stayed at Balmoral soon after the accession and found his sovereign to be ‘a very jolly chap but thank God there’s not much in his head.’ The Lloyd George verdict on George V and Queen Mary: ‘They’re simple, very, very ordinary people.’

==========

During the First World War, the King insisted on food rationing at Buckingham Palace: meals were cut from twelve courses to three and the use of wine or sherry was banned from cooking. Meat was to be served no more than three times a week and the use of excessive hot water for baths very much frowned upon. ‘I only get a hot bath once a week now,’ claimed the King, ‘– and – well, you just cannot lather soap in cold water, can you?’

==========

Prince Philip was also an enthusiast for order and economy. ‘We’re mocked for keeping our cornflakes in Tupperware boxes,’ he told me, ‘but it’s stupid not to.’

==========

Elizabeth II maintained her dignity all her life. There are no photographs of her in curlers or a bikini. There are not even any photographs of her and her husband kissing or holding hands. There are no records of Her Majesty using bad language or losing her temper in public or doing anything that could for a moment be described as undignified. ‘The media,’ Prince Philip said to me, ‘have done their best to turn us into a soap opera,’ but Elizabeth did nothing, ever, to contribute to that.

According to the novelist Graham Greene, ‘There is always one moment in childhood when the door opens and lets the future in.’ For Lilibet, the moment when her grandfather gave her Peggy was probably it.

==========

Princess Anne won the European Eventing Championships at Burghley on Doublet in 1971, leading the Duke of Edinburgh to compliment his wife on breeding both the horse and its rider.

==========

In September 1928, Winston Churchill – who would, one day, be Elizabeth II’s first prime minister – stayed at Balmoral as a guest of King George and Queen Mary. He wrote to his wife: ‘There is no one here at all, except the family, the household and Princess Elizabeth – aged 2. The latter is a character. She has an air of authority and reflectiveness astonishing in an infant.’

==========

‘Of course,’ said Mrs Rhodes, lighting another cigarette and putting her head gently to one side, ‘we were educated at home. The Queen and I were really the last generation of gels who didn’t go to school. We thought school would be ghastly. You’d have to play hockey. We didn’t want to play hockey. I had a French governess. The Queen and Princess Margaret had Crawfie.’ Mrs Rhodes smoothed out her skirt with an anxious hand. ‘I knew Crawfie. She was very nice really, but then she wrote the book. I haven’t read it.’

==========

In February 1937, Crawfie, along with Alah and Bobo and their young charges, moved from 145 Piccadilly across Green Park to Buckingham Palace. Number 145 had been a home, albeit a grand one staffed by eighteen servants. Buckingham Palace was the headquarters of an empire, with a staff in excess of four hundred. ‘I still recall with a shudder that first night spent in the Palace,’ said Crawfie. ‘The wind moaned in the chimneys like a thousand ghosts.’ Crawfie was disconcerted by the sheer scale of the place and not impressed by the (in every sense) Victorian quality of much of the accommodation. It was like ‘camping in a museum’, she said. The rooms were dark and musty.

==========

The girls enjoyed their guiding. ‘The Company was formed so that Elizabeth and Margaret Rose could meet and mix with ordinary children,’ Countess Mountbatten told me, with a charming little chuckle. ‘Well, there’s ordinary and ordinary, of course. I think the children were quite carefully vetted. I think they had to be “suitable”. But we did do ordinary guiding things. The long corridors at Buckingham Palace were ideal for practising signals and we went on wonderful expeditions in the Windsor forest, trekking and bird-watching and cooking sausages over the camp fire. The King’s Piper came and played for us and we did Highland dancing. That was fun.’

==========

Like her father and, to an even greater extent her royal grandparents, King George and Queen Mary, Princess Elizabeth was not given to public displays of emotion. She was, from an early age, self-controlled, self-contained, self-sufficient. Was that healthy? We might not think so, living, as we do, in the let-it-all-hang-out twenty-first century, but things were very different a hundred years ago. The ‘stiff upper lip’ wasn’t a joke then: it was a much-vaunted national characteristic.

==========

Sir Roy Strong, formerly director of the National Portrait Gallery and the Victoria and Albert Museum, met her on many occasions over the years. He told me, ‘She only ever really came to life when the dogs came into the room.’ He remembered meeting her once when she had just come from a large reception for leading literary figures. He asked her who was there. She said, ‘I don’t know. I forgot to wear my specs.’ If you asked her (as I did) about the presidents and prime ministers she had encountered across the years – everyone from Harry S Truman to Vladimir Putin – she would not be particularly forthcoming. But mention Bill Fenwick, the retired head keeper of Windsor Great Park or Nicky Beaumont, Clerk of the Course at Ascot for many years, and she would rattle away happily for minutes on end.

==========

Elizabeth II’s devotion to her father’s memory was lifelong, as was her admiration for Winston Churchill. I once asked her about her memories of VE Day. She said it was one of the days in her life of which she had the most vivid memories. She recalled stepping out onto the balcony at Buckingham Palace with her parents and sister to wave to the crowds cheering in the Mall. ‘My father asked Mr Churchill to join us. I think it is the only time someone from outside the family has appeared on the Palace balcony. It was an extraordinary day.’

==========

It was George VI who first described the House of Windsor as ‘the family firm’. It helped that – while, yes, they lived in castles and palaces and were surrounded by flummery and flunkies – there were only four of them, and they seemed … well, almost ordinary.

==========

It was George VI who first described the House of Windsor as ‘the family firm’. It helped that – while, yes, they lived in castles and palaces and were surrounded by flummery and flunkies – there were only four of them, and they seemed … well, almost ordinary. The King’s shyness, diffidence and stammer served to underline his decency. The Queen’s charm was simply irresistible. She wasn’t slim and chic and brittle (as ‘Queen Wallis’ would have been): she was soft and round, regal yet real, classy but comfortable and comforting. And the two girls – moving slowly through adolescence but still, mostly, seen dressed in matching outfits – looked to be model daughters: quite unspoilt and thoroughly wholesome.

==========

Her father was Supreme Governor of the Church of England, but not just in name. In his most celebrated broadcast, at the beginning of the war, he had said, ‘I believe from my heart that the cause which binds together my peoples and our gallant and faithful Allies is the cause of Christian civilisation.’ His daughter believed it, too. At his coronation – and hers – at the heart of the service, the sovereign is given a copy of the Holy Bible, with the words: ‘We present you with this Book, the most valuable thing that this world affords. Here is wisdom; this is the royal Law; these are the lively Oracles of God.’ Elizabeth II, not as a matter of form, but as a matter of faith, said ‘Amen’ to that.

==========

Lilibet’s adolescence coincided with the Second World War. She was a child of thirteen at the outset in September 1939, a woman of nineteen when victory came in the summer of 1945. In the intervening six years, she grew up: she was confirmed; she made her first broadcast; she shot her first stag; she inspected her first regiment; she launched her first ship; she learnt to drive; in her ATS training she tested herself, for the first time (perhaps for the only time), against contemporaries from ordinary backgrounds; indeed she mixed, after a fashion, with ordinary people for the first time; she rode her horses; she loved her dogs; she learnt to dance; she became a Counsellor of State and, in her father’s absence, visiting the Eighth Army in Italy in 1944, she performed her first constitutional functions, signifying the Royal Assent to Acts of Parliament. ‘There was always a strong sense of duty mixed with joie de vivre in her character,’ according to her French tutor, the Vicomtesse de Bellaigue. Princess Elizabeth had a good war, and she remembered it as, essentially, a happy time in her life.