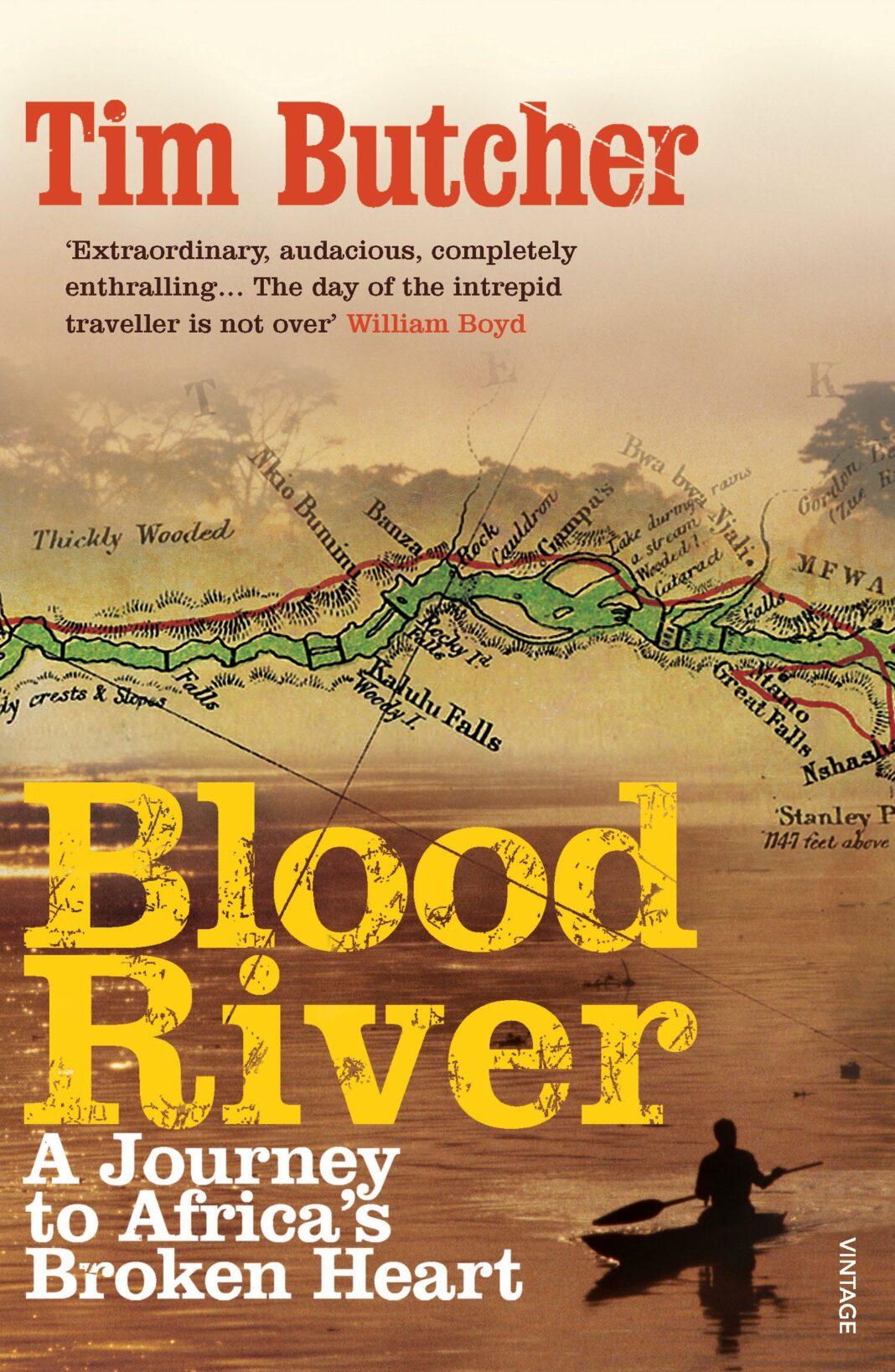

For me the Congo stands as a totem for the failed continent of Africa. It has more potential than any other African nation, more diamonds, more gold, more navigable rivers, more fellable timber, more rich agricultural land. But it is exactly this sense of what might be that makes the Congo’s failure all the more acute.

Modern hydrographical surveys show the outflow of fresh water from the Congo River is so strong that it has carved out of the seabed a submarine canyon 1,000 metres deep reaching almost 200 kilometres out into the ocean.

Since the 1994 genocide, Rwanda has been regarded by many outsiders as a tiny, frail country bullied by its larger neighbours. This is a grossly inaccurate generalisation. With a government now dominated by Tutsis, Rwanda punches way above its weight in regional affairs. There are clear parallels with Israel, another small country of people driven by the memory of mass murder committed against them to dominate its neighbours militarily, and the neighbour that Rwanda bosses most is the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The panhandle includes some of the richest deposits of copper, cobalt and uranium on the planet, a geological quirk that the early Belgian colonialists identified more smartly than their British counterparts.

The uranium for the atom bombs dropped by America on Hiroshima and Nagasaki came from a mine in Katanga, and it was Katanga’s vast copper deposits that really powered the colony’s growth when the reconstruction of Europe and Japan after the Second World War drove a surge in demand for copper.

The blessing of Katanga’s mineral wealth became its curse when Belgium granted independence to the Congo on 30 June 1960. While maintaining the illusion of handing over a single country to the black Congolese, the authorities in Brussels secretly backed the secession of Katanga from the Congo, financing, arming and protecting the pro-Belgian Katangan leader, Moise Tshombe, in return for a promise that the Belgian mining interests in Katanga would be protected. It was one of the most blatant acts of foreign manipulation in Africa’s chaotic independence period, and it culminated in one of the cruellest acts of twentieth-century political assassination, when Patrice Lumumba, the first Congolese national figure to win an election, was handed over by Belgian stooges to be murdered by Tshombe’s regime.

Several African nations were already moving into the Communist camp but the Congo was, in the eyes of the West, simply too important to lose so Brussels, with the connivance of Washington, engineered Lumumba’s arrest, torture and transfer to the capital of Katanga, then known by its Belgian name of Elisabethville, today’s Lubumbashi.

Leopold was able to present his colonial claim over the Congo as a fait accompli and, when the conference ended in February 1885, the Act of Berlin gave its legal recognition to the Congo Free State. With a surface area of more than three million square kilometres, it was claimed not by Belgium, but by the king himself. Never in history, neither before nor since, has a single person claimed ownership of a larger tract of land.

I have met British colonial types in Africa who scorn what Belgium did in the Congo and try to draw a distinction between the colonial system imposed by Brussels and that imposed by London. So much crueller than any British colony, they say, so much more brutal towards the local Africans, so much more manipulative after begrudgingly granting independence.

‘It’s the cassava,’ explained Tom. ‘It is the only staple for millions and millions of people across the Congo because it is the easiest thing to grow, but in terms of nutrition it is not really any good because it lacks many basic nutrients.

‘I come from east Africa, Kenya, where people die of starvation because of drought. There is never enough rain for the crops or the animals. But here in the Congo, they have all the rain they need, rivers full of fish, and soil that is unbelievably rich. If you stand still here in the bush you can actually see plants growing around you, the growth is that powerful, that strong. And yet somehow people still manage to go hungry here because of the chaos, the bad management. It breaks my heart to see all this agricultural potential going to waste.’

I looked at the sickly child and tried to think of another country in the world where a baby born in 2004 was more at risk than one born in the same place half a century earlier.

It was a sadly common feature of my journey through the Congo, the desperate willingness of people to cling to the old vestiges of order as an anchor against the anarchy of today. Here was a man who had not seen a train for years, yet he still kept his station house in a state of readiness, passing his time in an armchair on the platform next to the tracks that lay redundant and silent in the baking heat.

He reinstalled the river’s ancient name, Zaire, and named his country after it. Western Christian names were ordered to be replaced by authentic, tribal names, so Joseph-Désiré Mobutu became Mobutu Sese Seko Kuku Ngbendu Wa Za Banga, which translates as ‘the all-powerful warrior who, because of his endurance and inflexible will to win, will go from conquest to conquest, leaving fire in his wake’.

And he had distilled the quintessential problem of Africa that generations of academics, intellectuals and observers have danced around since the colonial powers withdrew. Why are Africans so bad at running Africa?

‘People who say there is no money in Africa are talking complete bollocks,’ Johnny said. ‘I have seen with my own eyes that there has always been plenty of money, whether it’s for diamonds, cobalt, safari hunting, whatever.

But the point is the money goes to only a few people, not to the country in general. If you think you can solve Africa’s problems with money, then you are a bloody fool. You solve Africa’s problems by creating a system of justice that actually works and by making the leaders accountable for their actions.

While outsiders led by Stanley can be blamed for creating this situation, the people of Africa must share responsibility for showing themselves unable to change it. The Malaysian naval officer on my river boat was right to ask why former European colonies in Asia have been able to develop since independence, while those in Africa have regressed. The cruelty and greed of African dictators is mostly to blame, but it is also true that the peoples of Africa have not been capable of working together to rein in the excesses of dictators.

One of the great fallacies about white rule in Africa was that when it ended, power was handed back to the people of Africa. I saw in the Congo how this simply is not true. At independence, colonial powers surrendered authority, but the point was that it never ended in the right place, back in the hands of the people. Instead it was hijacked by elites who publicly claimed they were working in the interests of their people, but were in fact only driven by self-interest.